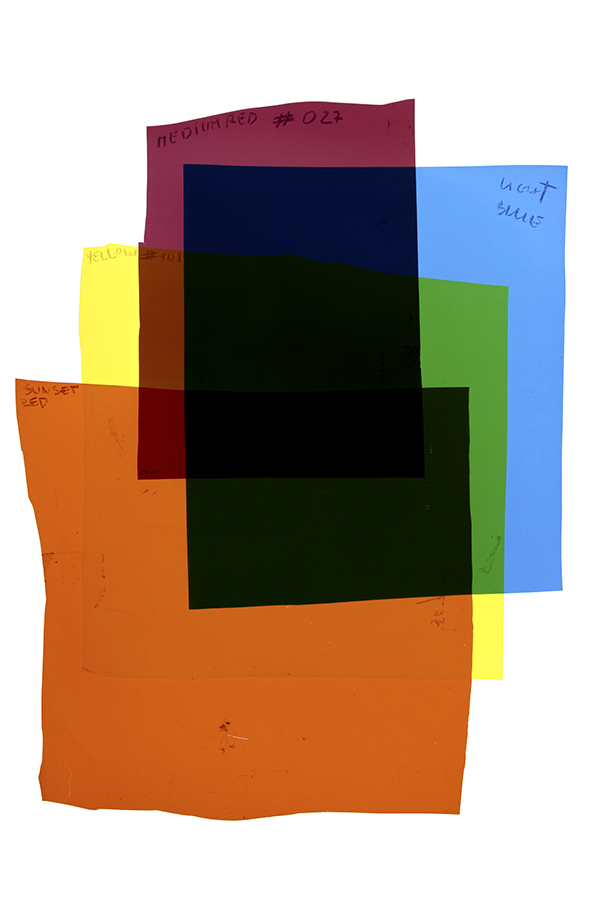

fig. 1: Play Time, 2015. Cesário M. F. Alves

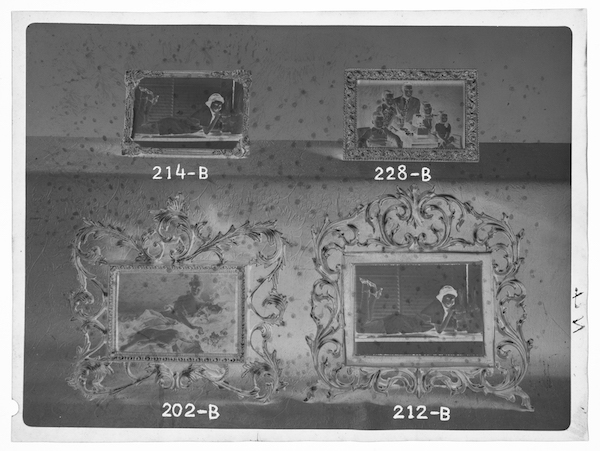

The 9×12 cm silver gelatine negative below, was obtained in a street market in Porto, Portugal, found among a set in the same format, depicting cast metal objects like picture frames, mirrors and chandeliers. Numbers related to each model engraved in the negative, indicate that we are probably facing a photograph for a commercial catalogue, a professional job commissioned by a maker or dealer of this sort of products.

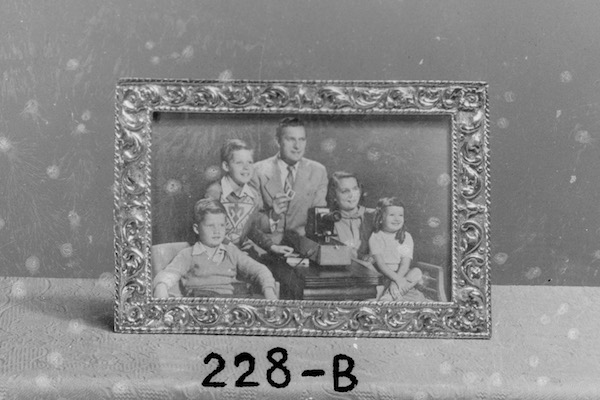

fig. 2: Original 9×12 cm negative

The negative releases the typical smell of acetic acid which plagues plastic cellulose acetate (a kind of plastic introduced by the photographic industry in early twentieth century), revealing a form of degradation known as the ‘vinegar syndrome’. It is encrusted with chemical crystallizations of plasticizer additives, taking the shape of small round eruptions on the film surface. They have conquered visual space over the silver grains, as if the photograph is inside a glass dome that has just been shaken.

Cellulose acetates were developed and perfected from the 1920’s onwards, intended to replace nitrate film, a much more unstable and flammable material, but it was soon discovered that the failure to preserve acetates under strict temperature and relative humidity control, would accelerate its deterioration (Fischer n.d.).

Rather than submitting this negative to a rigorous process of stabilization in a controlled environment, as could have happened in the hands of a conservation scientist, in this work it will be the subject of a poetical visual analysis, where the chemical degradation is assumed as a pictorial layer of the image.

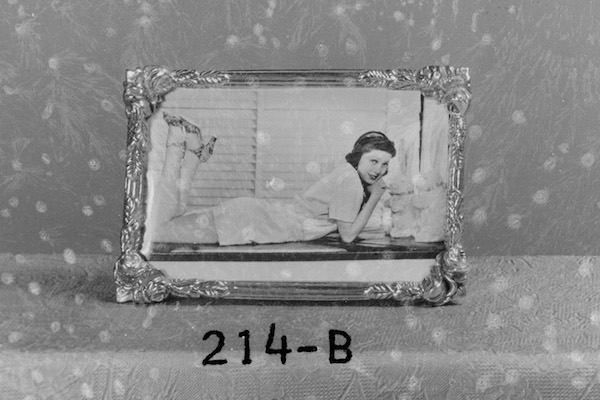

Despite being just one black and white negative it re-photographs other images inside frames (fig. 3), which seem to be industrial print reproductions of colour and/or black and white photographs; the kind that could be seen in calendars and other products of the printing industry, licensed from commercial image banks; generic multiples, which may have been reproduced thousands of times for different purposes.

fig. 3: Original 9×12 cm negative, inverted digitally.

Inside this catalogue photograph, other images become accessories and by-products of the business of making and selling frames. They inform the potential buyer about the function of this product, while at the same time suggest idealized models of what could be displayed. They are varied in subject and intended audience.

In organizing four models of frames in one shot, the photographer allows their comparison while saving time and film. Furthermore, by reproducing the set in black and white, he levels and attenuates the impact of each photograph inside of it. This serves perfectly well the purpose of selling monochromatic frames, if not the images inside of them.

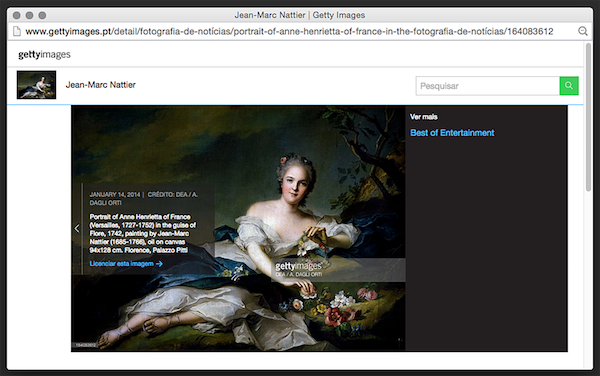

fig. 4: Anne Henrietta of France in the guise of Flore. Jean-Marc Nattier, 1742. (Nattier & Getty images n.d.)

Besides the photographer who made our 9×12 cm negative, there must have been a different photographer for each of the other photographs, reflecting specific formal and technical concerns, as well as intent. The pictures inside this photograph contain at least another three different narratives and a multitude of meanings radiate from them.

fig. 5: Fragment of original 9×12 cm negative, inverted. Detail 214-B

fig. 6: Fragment of original 9×12 cm negative, inverted. Detail 228-B.

fig. 7: Advert of Kodak Cavalcade projector, 1958. (Costin n.d.).

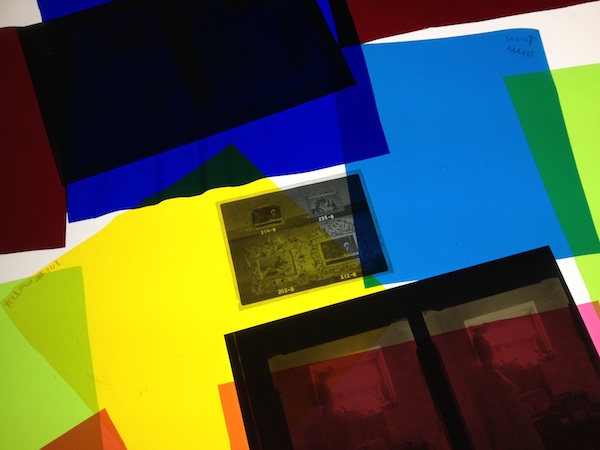

fig. 8: Play Time, composition experiment in the light-box.

The negative presented here as an object of research, is a professional photographic record primarily intended to promote commercial products, whose function could be to display and preserve the imperfect vernacular photographs made by amateurs. Ironically, the images it transports inside are meant to encourage the making of more photographs and teach what a good picture could be. However, the content and historical times of the images it holds, suggest other interpretations of their political and economic implications. Widespread representations of women and the family in certain times and geographies become exposed to analysis.

This work is presented as a photographic composition made on a light box, from a set of samples of light filters (fig. 1 and 8). The filters contain their number and identification: Medium Red # 027; Light Blue; Yellow # 101; Sunset Red. They were recycled from photography/cinema production sets and suggest cinematic environments. This mutating piece derives its name from the film by Jacques Tati – Playtime, from 1967 – which is also about the era and the colours that are suggested and simultaneously denied by the original black and white negative under observation.

………………………………

O negativo original que o objeto deste trabalho foi adquiridos sem qualquer informação associada sobre a sua origem, autoria ou identificação das pessoas representadas. Supomos que essas pessoas já desapareceram, mas se não for esse o caso e alguém conseguir identificar ou provar uma relação com elas, fazemos questão de os identificar, respeitando a autoria ou lhes devolver os originais.

The original negative included in this work was acquired with no information at all on their origin, authorship or identity of the people depicted in them. We assume this image was lost because whoever it belonged to disappeared. If that is not the case, and this work is seen by someone who can identify and prove a relationship to the people in the pictures, or the one who made them, we will gladly identify them, respecting their authorship or return the originals.